Learning the Ropes at SLAC’s Ultrafast X-ray Summer Seminar

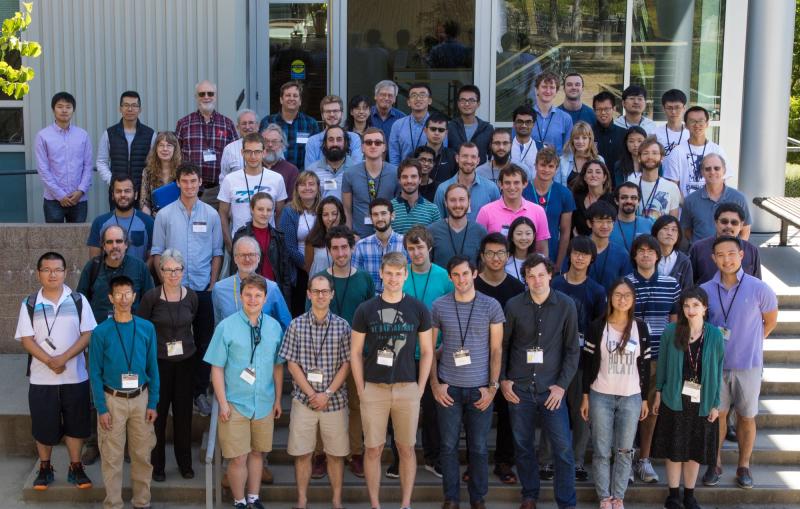

At UXSS, 90 graduate students and postdocs from all over the world got a crash course in how to do research at X-ray lasers such as LCLS.

SLAC’s recent Ultrafast X-ray Summer Seminar took the “teach a man to fish” approach: Rather than highlighting science done at X-ray free-electron lasers such as the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), it showed 90 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers from all over the world how to do their own.

The four-day seminar included talks by the scientists who run the six LCLS instruments and an exercise in which students split into groups and brainstormed mock experimental proposals for each of those instruments, which were evaluated by experts on the last day.

“Not only is this an intense learning experience, but it’s community building,” which is an important part of carrying out research, said Markus Guehr, a senior staff scientist at the Stanford PULSE Institute who chaired the seminar – and attended it himself in 2007 as a SLAC postdoc. “When you have an event where you can make new friends and at the same time do interesting science, what more do you need?”

The seminar was the latest in a series of ultrafast science summer sessions sponsored by PULSE and CFEL, the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science at Germany’s DESY lab. The first one was held at SLAC in 2007, and starting in 2011 the location has alternated between SLAC and DESY – the two labs where much of the seminal work in developing X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) has been done.

“So far about 600 students have gone through these seminars, and I think quite a lot of them now do research on XFELs,” said PULSE director Phil Bucksbaum. It would be interesting, he said, to see how many experiments at LCLS have included people who went through the program.

One of the goals of the seminar was to bring together scientists from two communities that don’t often interact: ultrafast laser science, which uses lasers to do research, and X-ray science, which uses X-rays from synchrotrons and other so-called light sources. Experiments at XFELs require both kinds of expertise.

Osama Alaidi, a graduate student from the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, said he appreciated the diversity of scientific specialties represented at the seminar. His own training is in X-ray diffraction, and for the brainstorming exercise he worked with a group that developed a mock proposal to study ultrafast changes in bacteriorhodopsin, a light-sensitive protein that certain bacteria use to capture energy from sunlight. It’s similar to the receptors that capture light in the human eye and a good model for studying light-induced changes in other systems, such as nerve cell signaling and photosynthetic energy conversion.

“We had someone who knows more about the protein and someone who knows more about the instrument in our group,” Alaidi said as a colleague explained their proposal at a poster session. “All together it made for a nice learning environment.”

LCLS interim director Uwe Bergmann told participants they should think about not only what can be done at LCLS today, but also about what XFELs will soon be capable of doing.

“LCLS will only get better as we go forward,” Bergmann said. “You should challenge our instrument scientists here not only with good ideas, but with new instrumentation and tools that you would like to see in the future.”

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.